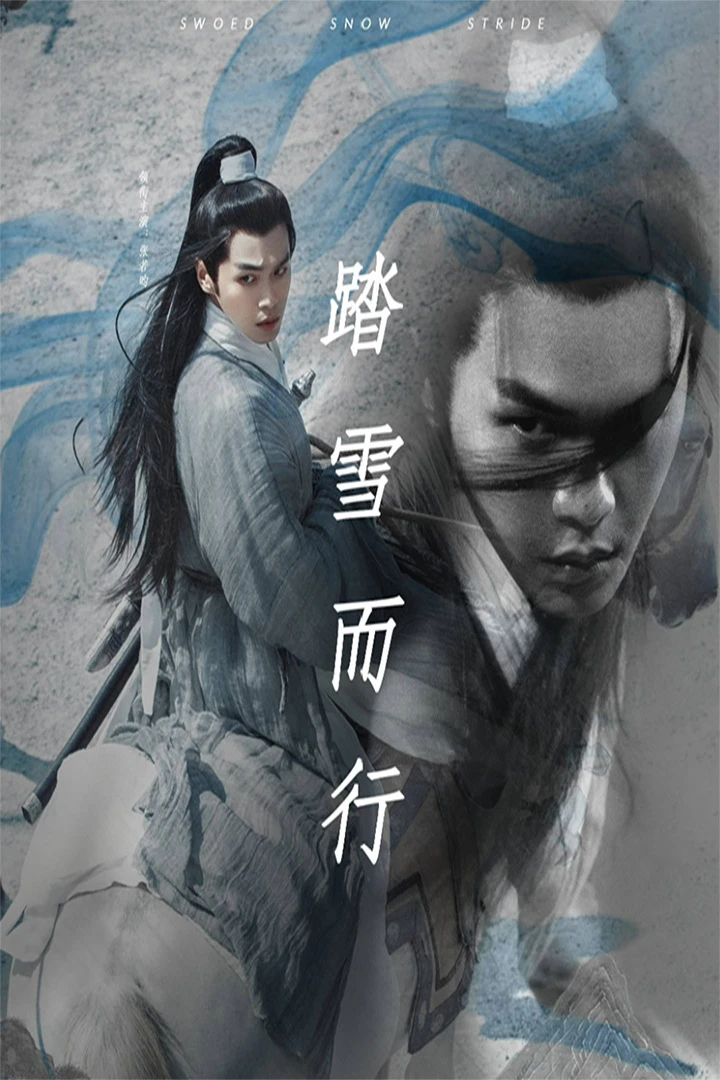

The 2022 wuxia drama “The Sword in the Snow” has garnered widespread acclaim for its stunning visuals, captivating dialogue. However, it is the show’s music that has truly captured the hearts of audiences, with its lyrics perfectly complementing the plot and its melodies evoking a sense of heroism and grandeur. The theme song “In This Lifetime” by Zheng Zhi has been praised for its perfect alignment with the show’s themes, embodying the spirit of chivalry and boundless vitality. The song “Walking in the Snow” performed by the male lead Zhang Ruoyun, with its lyrics “Endless resentment and grudges, let the world mock my foolish dreams… Iron horses and light cavalry sing praises, liver and gall weigh more than a thousand mountains; raising the frost and wine, severing the thoughts of the mundane world,” has been lauded for bringing back the long-lost flavor of the Jianghu (martial arts world).

When it comes to wuxia music, most readers’ first impressions likely revolve around the theme songs and insert songs of Hong Kong and Taiwanese wuxia dramas from the 1980s and 1990s. The 1983 TVB version of “The Legend of the Condor Heroes,” the first ancient wuxia drama introduced to mainland China, was divided into three chapters: “Iron Blood, Loyal Heart,” “The Weird, the Evil, and the Righteous,” and “The Duel on Mount Hua.” The corresponding theme songs, “Iron Blood, Loyal Heart,” “A Life of Meaning,” and “You Are Always Good in This World,” are still widely sung today. Other classics include “Swords Like a Dream,” “Love the Country More Than the Beauty,” and “Forgetting Each Other” performed by Zhou Huajian for the 1994 Ma Jingtao version of “The Heaven Sword and Dragon Saber,” the theme song “Carefree” performed by Richie Jen for the 1998 version of “The Return of the Condor Heroes,” and the theme song “A Laugh in the Sea” from Tsui Hark’s film “Swordsman.”

However, a brief review of the history of wuxia music reveals that as time progresses, the number of memorable and widely sung songs decreases. The 2001 Wu Qihua version of “The Heaven Sword and Dragon Saber” had songs with lower popularity compared to the previous version. The opening and ending songs of the 2014 Chen Xiao version of “The Return of the Condor Heroes” are likely forgotten by most people today. The 2019 version of “The Heaven Sword and Dragon Saber” directly used “Swords Like a Dream” as the opening song and “Forgetting Each Other” as the insert song.

This trend is not limited to Hong Kong and Taiwan. Since the beginning of the new century, mainland China’s film and television industry has been competing to remake Jin Yong’s wuxia works, with each adaptation accompanied by its own wuxia music. Taking “The Return of the Condor Heroes” as an example, there have been eight versions to date, but truly memorable and widely sung songs are few and far between. The ending song “Laughter in the Jianghu” from the 2006 version, performed by Zhang Jizhong, Hu Jun, Zhou Huajian, and Huang Xiaoming, was praised by netizens for having “a strong Jianghu flavor.”

Composer Deng Weibiao, who created the music for the Hong Kong wuxia film “The Haunted Town” and released the album “Original Motion Picture Soundtrack – The Haunted Town,” filling a gap in the history of Chinese film music albums at the time, stated in an interview with Beijing Youth Daily that there is no specific category of “wuxia music” within the industry, and there are no fixed “formulas” for its creation. “For us music students, it is just a means of musical expression that can appear in any genre at any time.”

However, regardless of the approach, wuxia music must first and foremost possess the essence of the Jianghu. Wong Kar-wai’s “A Laugh in the Sea” has been hailed by music critics as an elegy for the people of the Jianghu, exuding the tragic heroism and loneliness of the chivalrous. Wong Kar-wai recalled that when he was invited by Tsui Hark to compose “A Laugh in the Sea,” his work was rejected six times, each rejection igniting anger and frustration within him. Later, while reading “Critique of Chinese Musical Thought,” the phrase “great music must be simple” brought him a moment of enlightenment. After rewriting the song, he told Tsui Hark, “Old Tsui, this is the last time, the seventh time. Take it or leave it. If you don’t want it, find someone else.” This time, Tsui Hark was thoroughly satisfied.

Moreover, if a film or television song lacks a sense of patriotism, or if a musical work fails to express the spirit of wuxia, it will struggle to resonate with the audience, naturally leading to a decline in its popularity. In Deng Weibiao’s memory, people’s strongest recollection of wuxia music should be from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. After 2000, as the wuxia trend faded, the wuxia flavor in music naturally diminished. Taking “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” as an example, the music composed by Tan Dun focuses more on “emotion” – the feelings and inner workings of the characters. The soundtrack can be completely detached from the plot and stand independently from the film, making it difficult to associate with the previous wuxia concepts. The 2003 Su Youpeng version of “The Heaven Sword and Dragon Saber” features the opening song “Beloved” and the ending song “Falling in Love with Zhang Wuji,” which have less of the Jianghu atmosphere and more of love and affection.

In contrast, many songs in contemporary costume dramas are often criticized for forcibly playing with ancient style, resulting in “a pile of flowery words, lacking coherence,” devoid of chivalry, and even struggling to convey love and affection, merely imposing new words to express sorrow. The theme song “Cool” from the popular TV drama “Eternal Love” was criticized by many for having a pleasant melody but incomprehensible lyrics, with the line “How could you bear to leave in the previous life, this vast sea of the heart” being recognized as a prime example of piling up rhetoric but lacking substance.

The changing times have also brought new challenges to wuxia music. Veteran media person Meng Lun analyzed in an interview with Beijing Youth Daily that in the television era, audiences would sit in front of the TV waiting for the drama to start, watching from the opening to the ending credits. By the time they finished the entire series, they would have learned to sing most of the songs. Under the internet model, the fragmented viewing mode has made watching dramas simple and crude. Opening and ending credits can be skipped, and playback speed can be increased, to the point where one may not have heard a complete opening song even after finishing the entire series, rendering the music in film and television dispensable.

As times change, the medium to which wuxia music is attached is also evolving. One notable shift is the transition from film and television to the animation and gaming industry. The famous online game and mobile game series “The Legend of Sword and Fairy” has music that has even surpassed the influence of the game itself. Musician Li Guangping believes that some game soundtracks indeed possess the caliber of wuxia music from the past. In his view, some anime fragments, in terms of subject matter and style, closely resemble the features of past wuxia works and may even replace wuxia novels as the artistic form embraced by the new generation of young people. “Anime and game soundtracks can completely carry the wuxia dreams of the new generation. I have very high expectations for this. It is an important topic that we need to pay attention to in the future. Perhaps the next glorious era of wuxia music will be brought about by anime and games.”

Veteran media person Meng Lun believes that after bidding farewell to the era of solely focusing on traffic, music practitioners have more opportunities and motivation to create with a peaceful mind, which will lead to the production of more excellent musical works. While it may be difficult to give birth to another national-level wuxia music piece, regardless of the genre, as long as a song can move people and generate a strong resonance after listening, it deserves to be sung. No matter the era, people will always find a “wuxia music” that belongs to them.

In conclusion, the evolution of wuxia music reflects the changing landscape of Chinese popular culture. From the golden age of Hong Kong and Taiwanese wuxia dramas to the rise of mainland adaptations, and now the emergence of wuxia elements in anime and games, the genre has undergone significant transformations. Despite the challenges posed by the fragmented viewing habits of the internet era and the alleged decline in the cultural literacy of new-generation creators, the essence of wuxia music remains unchanged: to capture the spirit of the Jianghu, evoke a sense of patriotism, and resonate with the audience on an emotional level.